Lost Meadows

“The steady, quiet, and under-reported decline of our meadows is one of the biggest tragedies in the history of UK nature conservation; if over 97% of our woodland had been destroyed there’d be a national outcry. There exists a very real threat that we will lose our remaining meadows and the wealth of wildlife they underpin unless we learn to love, cherish and protect them."

Dr Trevor Dines, Plantlife Botanical Specialist

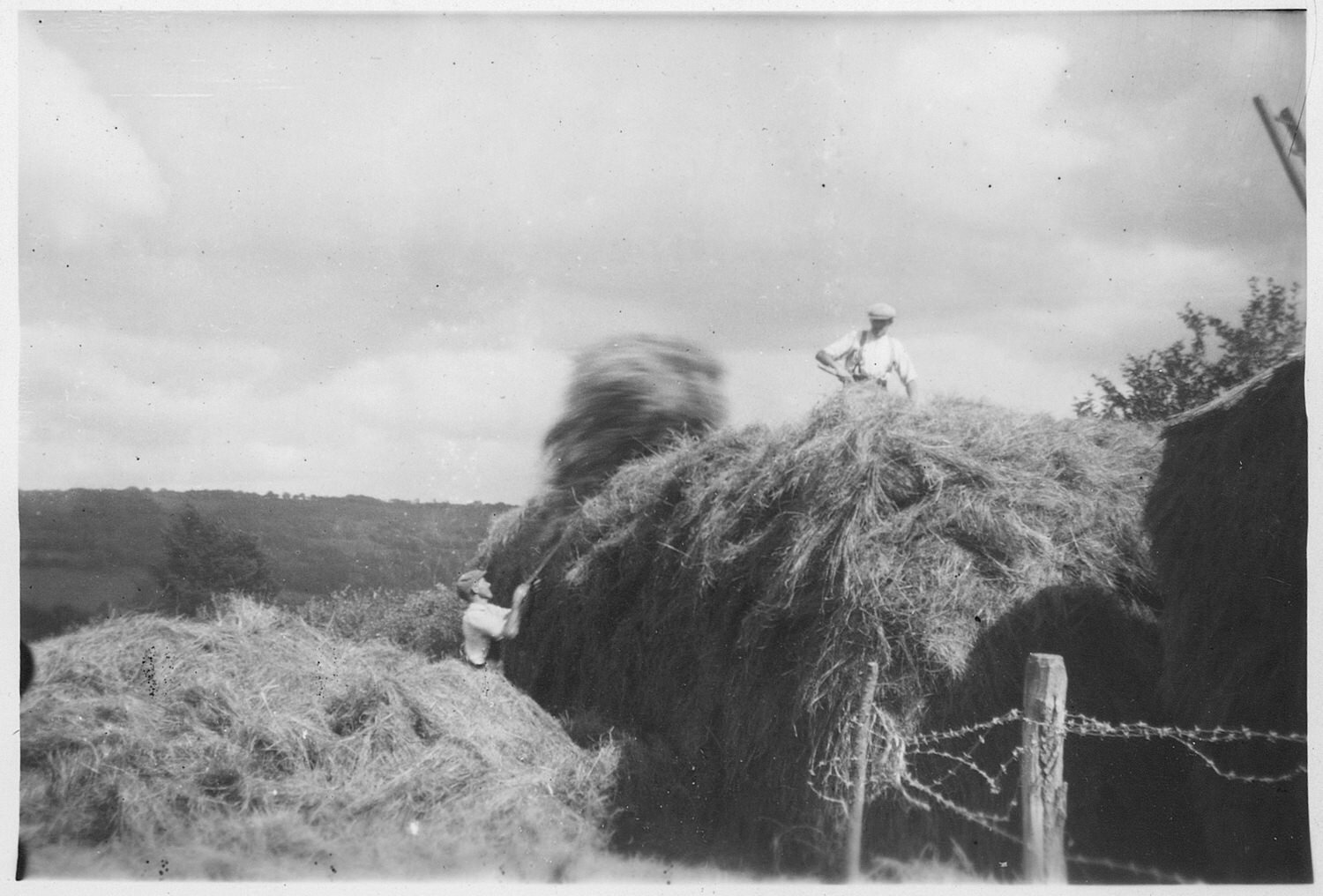

Stepping into a meadow is like stepping back in time, into a world illustrated by the impressionists and celebrated by poets. These semi wild and beautiful acres were once the heart of our rural communities, providing employment and food for livestock. People grafted together for summer harvests and celebrated with haymaking ceremonies and festivals. Traditional haymaking allowed nature to thrive, with only one late summer harvest. The flower rich meadows bloomed all summer long and created wildlife havens with hundreds of species of flora, which in turn supported thousands of different types of invertebrates, insects and other mammals.

Since 1930 UK meadows have declined by 97%. Around 40% was lost during WWII, when six million acres of farmland were ploughed to make cereal. Farming then became a lot more intensive and pesticides were introduced. This, along with the development of land for property, has driven the decline of our meadows. Historically our gardens would also act as mini meadows, full of long grass, plants and flowers which are good for pollinators. Now, plants are often decorative, chemicals are used and the grass is mown regularly or turfed over.

Meadows are important for combatting climate change as they store carbon within their soil. They support a vibrant eco-system and help maintain a healthy planet. Due to the decline in meadows, some grassland species are already extinct and many are endangered. More widely, the UK now ranks as one of the 10 worst countries in the world for biodiversity loss with only 50.3% left intact. In this country meadows host more vulnerable species than any other habitat, making them one of the most important & precious ecosystems we have

© Images courtesy of Totnes Image Bank.

(L)Tea in harvest field at Higher Lake Farm c1930. 2L J.T.Manning, right Mrs Manning and daughter Ruby.

(R) Haywain at Seccombe Farm, Blackawton, c1940. Geoff Pillar (bro in law of Edith Tucker, Instart), Edith James, Jean Forsyth, John Kelland (farmer).

During the first UK lockdown my daughter, Lila, and I spent time in our local meadows, which were just bursting back into life after a long winter. One day we learned of future development plans for the meadows closest to me. They had been sold with plans to build 85 new houses.

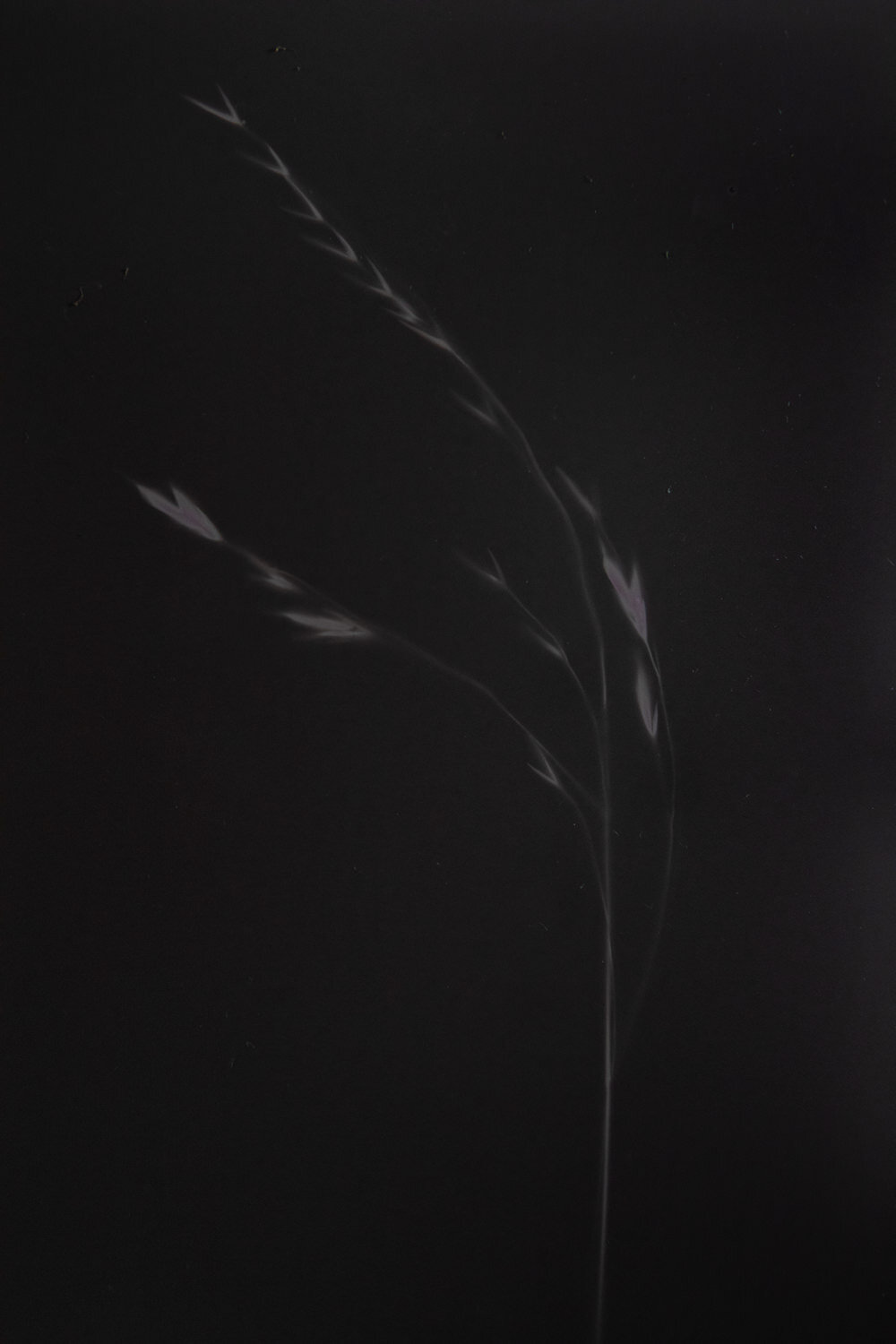

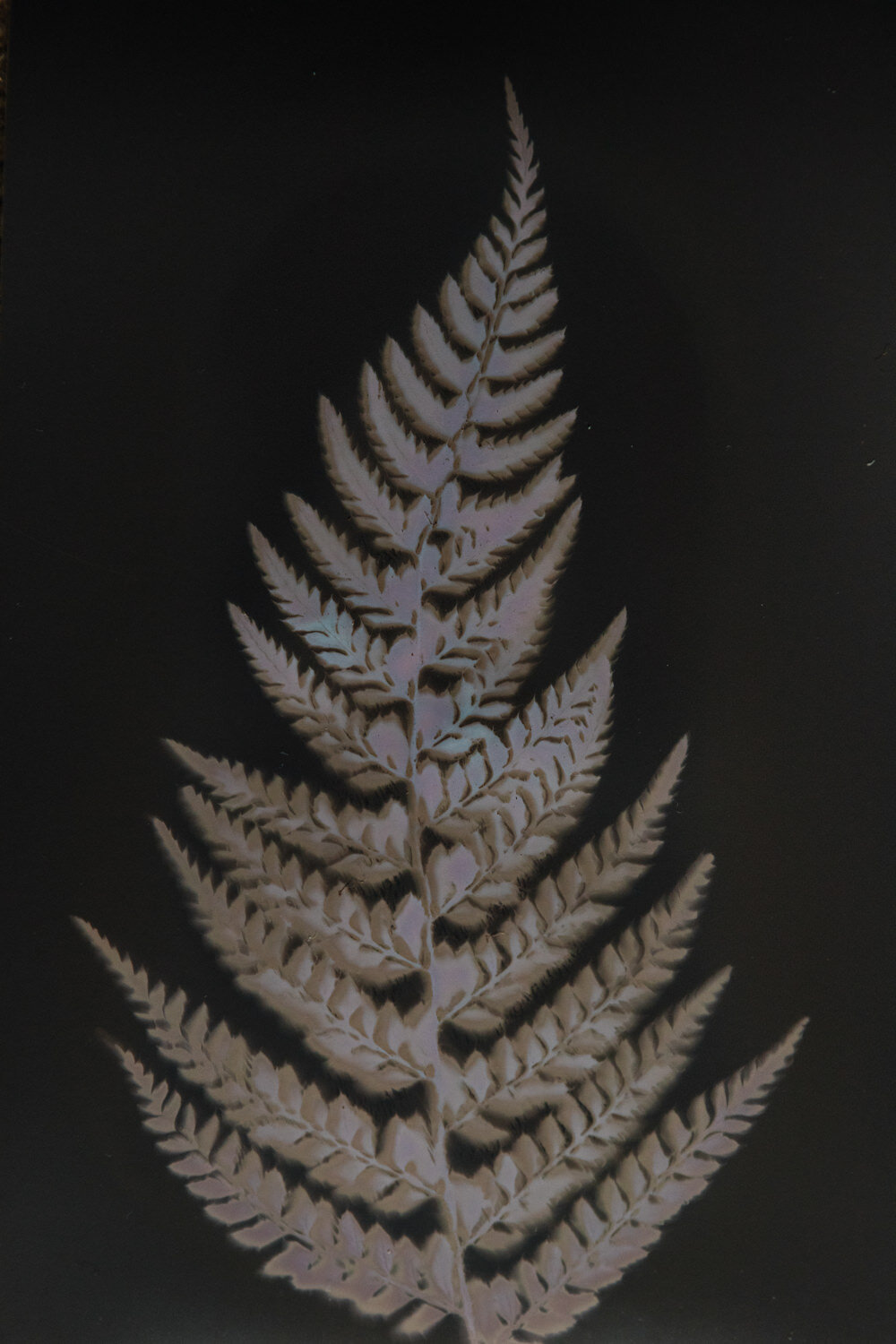

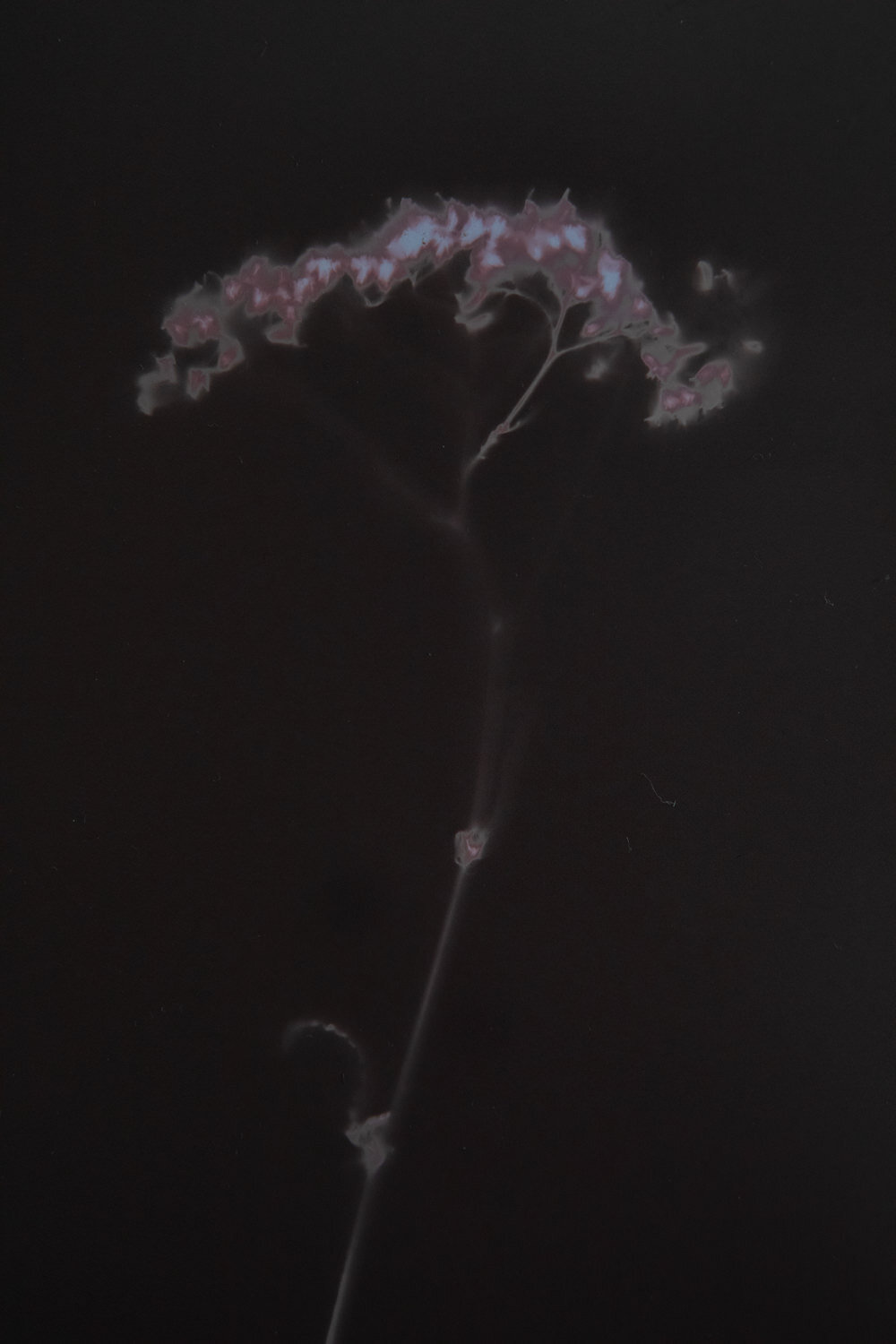

We made lumen prints from some of the many plants, flowers & organic material we found. One small, rewilded meadow in our local village lists over 60 different plant varieties alone.

Image - Ash Leaf

“A lawn when you come to think of it, is nothing but a meadow in captivity. Modern lawns have little or no wildlife value. Most are green deserts, marinated in chemicals, comprised of only a few garden species, and shorn stupid once a week in summer. But in the middle age, a lawn was more like a meadow; it was a ‘flowery mead’, bursting with perfumed wildflowers and herbs and grasses. These gorgeous semi-wild acres were an integral part of medieval life, used to their full for walking in, dancing on, sitting in. And in houses and castles where privacy was hard to find, they were the perfect places for lovers to share secluded passion”

— John Lewis Stempel, Meadowland

The gallery above features images of: snowdrop, wild strawberry, meadows grass, wax cap mushrooms, fern, cow parsley, oak leaf, wood pigeon feather, bramble, yellow rattle, alder leaf and sycamore leaf.

Image opposite - Wild Poppy

Farmland flowers have declined by 96% in 200 years. This includes flowers found in traditional wildflower meadows (haymeadows) and those found on arable farmland or Cornfield. Arable flowers include wild poppies which are one of the fastest declining plant species in the UK. Wildflower meadows contain around 140 species of flora. Arable farmland is home to 120 wildflower species, including cornflowers & poppies. Both are losing biodiversity through the intensification of farming practices and pesticide use.

Flora supports around 1400 different species of insect & invertebrates, including pollinators. Declining flowers & plants impacts an entire eco system.

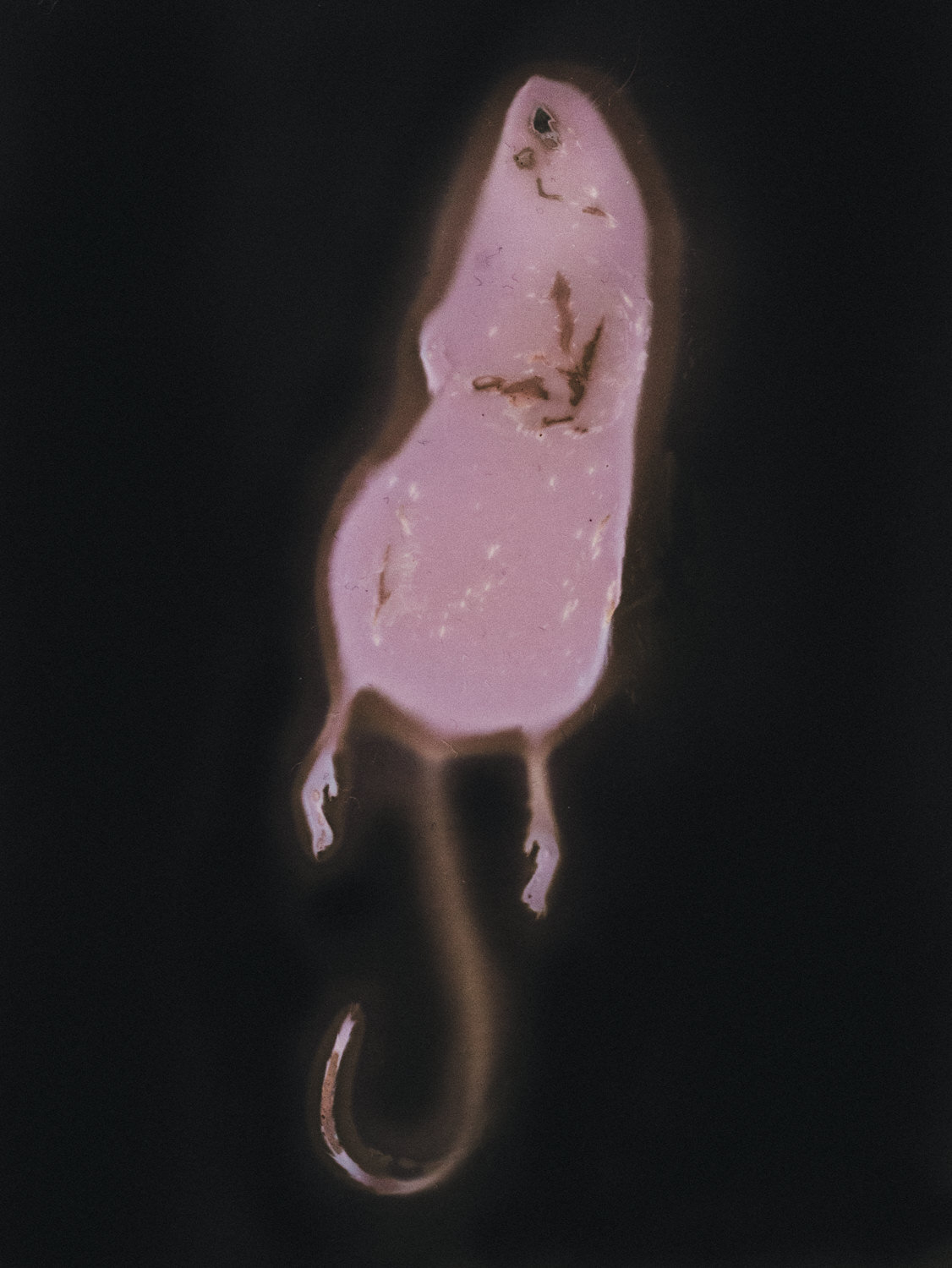

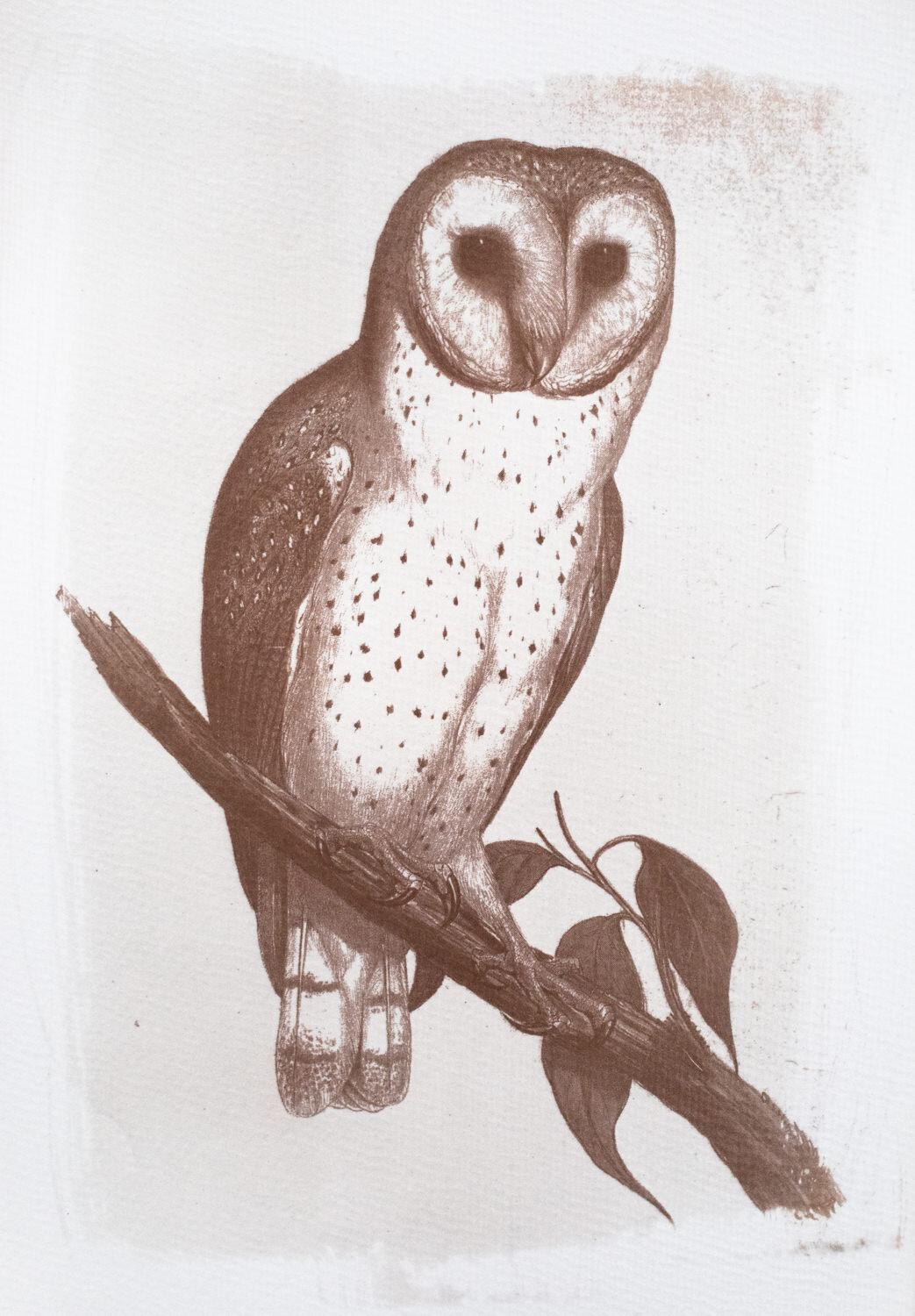

A State of Nature Report from 2013 estimates that invertebrates in the UK have declined by 60-70% in recent years. With the loss of this rich habitat, many iconic species of the British countryside are following suite. The celebrated Skylark, also a ground nesting bird, is now in rapid decline with a fall of 54% between 1976 – 2001, Barn Owls saw a 70% loss between 1932 and 1985, Harvest Mice have declined by 70% since 1970, the population of Hares has decreased by 80% in 100 years and there are now only one million of our beloved Hedgehogs remaining in the wild.

This gallery contains images that I have created of endangered & extinct species using historical images sourced from the Biodiversity Heritage Library. I have listed the species below with their rate of decline;

Skylark - declined by 75% between 1972 and 1996. Population still declining

Farmland Flowers - declined by 96% in the last 200 years

Bees - One third are in decline. Some species, such as the short-haired bumblebee (dependent on grassland habitats) are already extinct

Butterflies - 70% of species are declining and some species are already extinct. The Mazarine Blue butterfly (commonly seen in European meadows) became extinct here when haymaking practices changed.

Hedgehog - Fewer than a million hedgehogs remain. This is due to habitat loss and food scarcity (loss of insect & invertebrates)

Spotted Flycatcher - declined by 87% since 1970

Corn Bunting - declined by 88% between 1967 and 2012

Wild Thyme - Classed as vulnerable and almost completely extinct in arable habitat. A main food source for butterflies

Grey Partridge - declined by 91% between 1967 and 2010

Pheasant’s-eye - declined by 92%

Turtle Doves - declined by 93% since the 1970’s

Harvest Mice - declined by 70% since the 1970’s

Treesparrow - declined by 93% between 1970 and 2008

“Rewilding encourages a balance between people and the rest of nature so that we thrive together. It can help reverse species extinction, tackle climate change and improve our overall health and wellbeing.”

“What would it take to become a good ancestor? I keep imagining the moment 30 or 40 years from now when these girls of mine are holding their own children close in a meadow like this and the sense is not of crisis or extinction but of planetary abundance and futurity. How do we fill these next 30 or 40 years to make that dream a reality?”

— Ashish Ghadiali, Writer & Activist

Environmental organisations are calling for 30% of the land & sea of Britain to be restored or rewilded by 2030. This would give nature a chance to recover. Rewilding can include many things, from creating vast wildlife corridors to making a wildlife-friendly garden. A national movement of meadow makers, led by Plantlife, is hoping to restore 120,000 acres of species rich grassland in the UK.

Lila & I visited rewilding projects and spoke to meadow makers, farmers, gardeners and local people in the meadows we visited. I wanted to find out more about rewilding and see firsthand the benefit these projects are having.

“Stretching over 70 acres, Goren Farm is nestled in the Blackdown hills AONB. The farm is mainly species rich hay meadows, with some woodland and traditional cider orchards. It is quite rare to find such a large area anywhere in the country.

No seed has been introduced and all the species have occurred naturally in the meadows. From 1991 all the meadows were being cut for hay every year and the crop mainly removed and sold. Since 2003 we have managed the farm for the wildflowers rather than hay and this management focuses on creating the right environmental conditions for targeted species to spread, or not. This involves varying the cutting times, rolling and harrowing the fields, fertilizing, grazing. We harvest the seeds from our fields to provide species for local habitat restoration. Our harvest methods include hand picking, brush harvesting and green hay spreading.

Whilst the fields are full of wildflowers which look amazing they have an overall positive effect both below the ground and in the air. They are helping to reduce the impact of climate change and flooding and provide valuable food plants for insects, birds and mammals. We only harvest a small proportion of these meadows each year in order to not upset this balance.”

— Julian Pady, Farmer

(Images below from the Goren Farm family archive 1958 - 2001)

“I'm Audrey Compton and I farm Deer Park Farm with my husband, John Whetman. We are active farmers - but we are also old enough to remember what meadows were like in the 1950s, before ploughs, fertilisers and sprays changed our landscape for ever. My sister and I used to take a 'long-cut' through a small meadow on our way home from primary school. There was a tiny stream shimmering through the middle, with a rotting wooden bridge; there were as many flowers as grasses and the scent of meadowsweet still takes me back there in an instant. The meadow was humming with insects - mysterious things that crawled into our ankle-socks and stung us in retribution; beautiful tortoiseshell butterflies looking crazily exotic; warm and chubby bumblebees searching for the tastiest flower. Occasionally there would be a few cattle grazing there and we'd cross the stream cautiously in case they resented us. The hedges were massive, part of the field really, creating multiple shade and textures. It was magic! But just a few years later, it was a housing estate.

We are incredibly fortunate to have a marshy field at Deer Park farm that has, with a little grazing, become very similar to that magical meadow from my childhood. Our 40 acres of farmland are home to 350 species of wildflowers. We also have an abundance of rare waxcap mushrooms, with around 90 fungi species. Because of this the farm has national importance.”

— Audrey Compton, Deer Park Farm

“Standing in the middle of a lifeless barren arable field, devoid of insects, butterflies and bees - I knew I had to do something. Five years on, having been given the opportunity, the same piece of land is now rich in native wildflowers and grasses including knapweed, meadowsweet, purple loostrife, meadow cranesbill meadow vetchling, quaking grass, musk mallow and hairy tare. It is vibrant source for invertebrates with wasp spiders, six spot burnet moths, silver washed fritillary to name a few. Barn owls, skylarks, field mice and bats are all regular visitors. Our meadow is not cut for hay as we’ve found taking away important flowers and seed in mid summer detrimental to wildlife. During the winter months it is grazed by our retired horses, providing them with a healthy diet and winter habitat for birds and insects. Year on year the meadow improves as more plants emerge from the seed bank in the soil. Nature just needs to be given a chance to thrive.”

— Jenny Rogers, Ash Tree Farm

“I worked in this meadow for a year as part of a team restoring & maintaining this natural habitat. I now work as a herbal practitioner. There are so many traditional wild herbs which are hard to come by now due to the loss of habitat. The plants we are losing are precious and many have medicinal values as well as being important for biodiversity. Meadows are an important host for many plants & mycelial networks to thrive. We should be protecting and studying these spaces and the networks of life that exist within them”

— Rebecca Clelland, Dartington Meadow & Pollinator Sanctuary

“Because of the rapid destruction of meadows in the UK, meadows like these are vestiges of an era of beauty and diversity that will take us generations to re-establish. Protecting and promoting these sanctuaries seems like a duty to the planet and all life that inhabits every niche it can find. Anyone who has seen the fascination and joy in a child's face exploring a meadow would agree that there are endless wonders to discover in meadows, and endless things we can learn about ecology that are priceless. All the magic of creation is contained within even the smallest seed.”

— Ross Perrett, Dartington Meadow & Pollinator Sanctuary

“As a farmer or custodian of the land I manage it seems obvious to me to stop fighting against the natural occurrence of beneficial wild habitat. 70% of my land is suitable for productive grassland farming, the remaining 30% wants to revert back to its natural untamed state. A large part of modern intensive agriculture is centred around spraying, draining and cultivating these ‘less productive’ areas. I’m not fighting them, just embracing their benefits and using native livestock to manage them as generations before us did.”

— Sam Bullingham, Farmer from Taw River Dairy

It is estimated that now only 26,000 acres of wildflower meadows remain.

We have over 12 million acres of private gardens.

By creating a wildlife-friendly garden you can help to counteract some of this tragic biodiversity loss.

“Hope is not a lottery ticket you can sit on the sofa and clutch, feeling lucky. It is an axe you break down doors with in an emergency. Hope should shove you out the door, because it will take everything you have to steer the future away from endless war, from the annihilation of the earth’s treasures and the grinding down of the poor and marginal... To hope is to give yourself to the future - and that commitment to the future is what makes the present inhabitable.”

- Rebecca Solnit, Hope in the Dark

“We are lucky as we have a lovely big garden. Some of this is rewilded as a small meadow, which the butterflies love, and this year I rewilded a tiny patch of the garden - my childrens old sandpit - into this colourful wildflower garden. It’s incredible and the bees absolutely love it!! I used a packet of seeds, a wildflower mixture. It’s really something anyone can do and it’s such a joy to look at from my kitchen window.”

— Susan Painter, gardener

“I grew up in “the olden days” surrounded by wild meadows and a diverse array of animals. I felt connected and intrigued by the magical effects they seemed to have on both myself and the environment surrounding them. This has provided me with a visual anchor that I have always been able to hold onto. The swath of flowers and grasses remind me of a marching band, in full swing, leading an infinite parade of some of the most important elements of our existence as human beings. It’s fast becoming a forgotten and neglected chain that has weakened, lost links and suffered as a result of abuse from one of the very species that is reliant upon it. As a humbled member of that species, I strive to become a strong link in this chain for the sake of my children and the speedy recovery of our long suffering planet.

I returned to my countryside roots 10 years ago and found a little plot of land in Devon with rewilding in mind. I also met Emily, my wife, around that time and we began learning about traditional farming and forgotten crafts together. Our first course was beekeeping. It has been a magical journey that we have been able to share with our two children.

We have since rewilded several areas and have a little garden patch that the children love. They plant seeds and watch them grow, they understand about the importance of healthy soil and are not afraid of getting muddy!

With the help of like minded friends we now run workshops here too, sharing ancient skills and lost knowledge whilst exploring the wonders of nature and bringing us closer to our roots as human beings.”

— Robin Fox, Rewilder & owner of Foxworthy Farm (archive photo from 1981)